Sunday, May 7, 2017 |

Gained in Translation

How, far away from his fatherland, a German scholar found comfort in Tagore’s land, among his works and his people. V. Kumara Swamy has the story

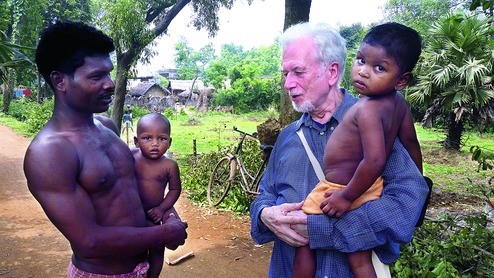

A LANGUAGE OF HIS OWN: Martin Kaempchen interacting with people in and around Santiniketan

For most Germans, Rabindranath Tagore with his flowing white beard and soulful eyes was more of a mystic from the East than a literary figure. The poet had visited Germany thrice between the two World Wars and that image endured for quite a few years.

The perception underwent a noticeable change only in the Nineties, when Martin Kaempchen started translating Tagore’s original works with all their delicate nuances into German.

Apart from Tagore, over the last 30 years, Kaempchen has translated the works of Swami Vivekananda, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, Mahatma Gandhi, and even found time to write a novel, a couple of short story collections and a children’s book. “You can say I have been very busy,” says the 68-year-old who was in New Delhi recently to present some of his books to President Pranab Mukherjee.

Kaempchen speaks with a very thick German accent, something he is very conscious about. “I also speak Bengali with a thick accent. You cannot blame me. I learnt Bengali when I was in my early thirties. I am fluent in Bengali but not without mistakes,” he says, wagging his finger.

His is a familiar figure in Santiniketan and the surrounding villages dominated by Santhals. He can be seen cycling down the dusty roads looking every bit the single-minded professor with his snow-white hair and neat goatee, interacting with just about everybody. “I like talking to, what you may call ‘simple people’ in their own language.”

Kaempchen first came to India in 1971 and stayed for three months. He returned in 1973 and the original plan was to live here, learn about Mahatma Gandhi and then go back to Germany to pursue his dream of becoming an opera and theatre critic. But that never happened. He kept extending his stay in India year after year.

The interest in Bengali and Tagore was stoked by a gift. In 1976, after teaching German for three years at Calcutta’s Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, he was presented with a copy of Tagore’s Gitanjali by the students. Kaempchen told himself that one day he would read the book in the original Bengali.

But that didn’t happen immediately. “I must say that I first fell in love with the people of Bengal more than the language, and once I started learning the language it opened my eyes to the world of Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and Tagore.”

He spent three years at Madras University, where he did his PhD in Comparative Religion. Soon after, in 1980, he went to Santiniketan to teach. And that is when he started taking lessons in Bengali. “I had a teacher who used to tutor me for two hours every day for almost two years,” he recalls.

Working at Visva-Bharati University as a part-time teacher had its advantages. Kaempchen had plenty of time to do things he wanted. And as his Bengali improved, the impulse to translate Tagore into German grew stronger.

“Tagore translated his own poems into prose. It was lyrical but it was prose. There was no rhyming or stanza in the translated versions. My idea was to translate a poem into another according to the poetic scheme. It is only then that the soul of the poem reveals itself. The flower of the poem can bloom,” he says mimicking the unfurling of a flower with his hands.

Translating, apparently, wasn’t easy in the initial days as he would constantly go back to improve his work. “Tagore may have written a poem in an hour, but I may have taken six months to translate the same.” Capturing the exact meaning of a Tagore poem in German still does not come easy, but Kaempchen says when he does get it right it is a special feeling. “When I am able to capture the soul of the poem, I feel like I am the co-translator of the poem along with Tagore. I sometimes feel like I am his brother or maybe it is a father-son relationship.”

Kaempchen is a regular contributor to one of Germany’s largest selling dailies, Frankfurter Allgemeine, where he writes mainly on Indian culture. “Many Germans consider India the cradle of humanity, where religion, culture and pure humanity is at home. I provide a perspective.” He, however, concedes that India’s image as a “tolerant, accommodative and a multifaceted pluralistic society” has suffered in recent years due to violence against minorities.

He has continued to do his bit for the less privileged, though. He has taken up several developmental projects in some Santhal villages around Santiniketan. He has opened schools and encouraged tribals to take up economically sustainable livelihoods.

From what he says, not everyone is comfortable with these efforts. Many years back, a colleague at Santiniketan alerted the police that Kaempchen might be indulging in Christian missionary activities. “I told them if they find I have converted even a single person, I would leave India forever.”

A practicing Christian, Kaempchen proudly declares that he has no problem visiting temples and meditating before Hindu idols. “Recently, I went to a church in Shimla in the morning and then participated in a prayer and lunch with members of the Ramakrishna Mission. A few days later I was at a Kali temple in Himachal, meditating. I am in complete harmony with everything,” says Kaempchen, who is currently parked in Shimla, as Tagore Fellow at the Indian Institute of Advanced Study.

The Indophile who calls himself a “free spirit” likes travelling and says this is one hobby he would like to continue. These gallivantations, however, come at the cost of time spent at his much-loved Santhal villages. In fact, he hasn’t been “home” for the last four months. “This is probably the longest I have been away from Bengal,” he says and shows off the call list on his phone – an endless scroll of names and numbers of villagers who call him and enquire about his long absence from Santiniketan. “No matter where I am, I want to go back to these villages,” he thinks aloud.

Well, poems always benefit from the occasional hard punctuation. Helps rein in creative thought and energy.